Warning message

- Last import of users from Drupal Production environment ran more than 7 days ago. Import users by accessing /admin/config/live-importer/drupal-run

- Last import of nodes from Drupal Production environment ran more than 7 days ago. Import nodes by accessing /admin/config/live-importer/drupal-run

Unpublished Opinions

Should we cry over Crimea?

Over the centuries, Russia has attempted to control Ukraine as a fore-post or buffer against attacks of Scythians, Polovtsev, Tatars, Mongols, Ottomans, Germans – any outer threat. Crimea has been a key element in this strategy. Apart from the six decades between 1954 and 2014 during which Crimea was officially part of Ukraine, Crimea has been "Russian" since Catherine the Great, (Empress 1761-97).

Russia's capacity to reach the sea is limited by geography, so ports in the north and south seas, leading to oceans, are crucial. Before the current conflict erupted, the Crimean port Sevastopol was a strategically important base for Russia's naval fleet, in addition to being Russia's only warm-water base. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, a 1997 treaty with Ukraine, along with its subsequent extension, allowed Russia to keep its Black Sea Fleet largely intact and to lease and occupy the base at Sevastopol until 2042.

My understanding is that Crimea prior to WWII was populated mostly by Tatars (Sunni Muslims) with many minority mixes (Russians, Ukrainians, Greeks, Armenians, etc). After WWII, on the pretext that the Muslims cooperated with the Nazis, Stalin ordered the Tatars to depart from Crimea (voluntarily or by force; I understand that most moved to the Tatar Autonomous Republic, reborn in the late years of the 20th Century as Tatarstan). Other peoples, e.g. Greeks and Bulgarians, were also driven out of Crimea. Whereupon masses of ethnic Russians, mostly farmers, relocated to the Crimea. This turned out to be smart politics – from the mid-fifties of the 20th Century, the Crimean population would vote for being Russian or joining Russia, as needed.

Tatars, who are mostly Muslim, have long regarded Crimea as their national home. But they have suffered from discrimination that continued to the dying days of the 20th Century. Their plights and their rights have largely been ignored by the media. For some insight into their situation, take a look at

http://www.economist.com/blogs/easternapproaches/2014/09/russia-and-tatars and http://www.economist.com/news/international/21654671-life-mustafa-dzhemi....

Subsequent to the collapse of the Soviet Union, some Tatars tried to return to Crimea, with mixed results. They now make up about 12% of Crimea's population – massively outnumbered by the ethnic Russians who dominate the peninsula. The Tatars have not been able to reclaim the lands that their families possessed before the deportation. During the Stalin era, hundreds of mosques were closed, Muslim clergy were executed, and the celebration of Muslim holidays were banned. After their return from exile, the Crimean Tatars attempted to restore some of the old mosques and to build new ones, provoking debate and hostility from the ethnic Russian majority in Crimea. While some aspects of the attempted resettlement of Tatars in Crimea remain in doubt, it does not seem probable that the Russian majority will readily grant many concessions to the Tatars.

Totally out of the blue, and seemingly as an unnecessary gesture, in 1954 Khrushchev “made a gift” of Crimea to Ukraine. (The rationale for the gift appears to have been twofold: (i) to add Russian speakers and sympathizers to the population of Ukraine; and (ii) to counter the nationalists from Halychyna and other parts of Ukraine who have historically been hostile to Russian interests.) Whereupon until its annexation by Russia in 2014, Crimea was officially Ukrainian; the people of Ukraine got used to it; geographic maps showed it. Ethnic Ukrainians settled in Crimea; they at present constitute about a quarter of the Crimean population. Even though ethnic Russians comprise close to 60% of the Crimean population, nevertheless when Putin reclaimed Crimea, this looked to most Ukrainians like robbery, history notwithstanding.

Assuming that overt acts to further any Tatar claim in or to Crimea will be constrained over the predictable future, the remaining competing direct interests in Crimea are limited to those of Russia and Ukraine, while the west has a derivative interest in opposing any further Russian expansion.

The key question re Crimea is thus whether the 2014 Russian annexation will stand indefinitely, or whether it can be reversed, and Crimea returned to Ukraine.

There are two schools of thought on the question.

Those who consider that Ukraine’s interest in Crimea is not dead rely upon international law and international strategic motivation. In their view, Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea represents a serious blow to the security structure that has grown up in Europe since the Second World War. It is the first annexation of European territory since the end of the War. The annexation violates the United Nations Charter, the Helsinki Accords that led to the end of the Cold War, the treaty of 1991 dissolving the Soviet Union, which explicitly re-affirmed the boundaries of the former Soviet Republics, the Treaty of 1997 between Russia and Ukraine, which while granting Russia a 15-year lease of the Sevastopol naval base, also explicitly re-affirmed the boundaries of Ukraine, and the Budapest memorandum of 1994 that guaranteed the territorial integrity of Ukraine. If the annexation is recognized or tacitly accepted, then it will be tempting for Russia to do the same thing in Belarus, the Baltic republics, Kazakhstan and Georgia. In these countries, Russia can trot out similar historical arguments and proffer the same claims to protect the rights of Russian speakers and Russian compatriots, which latter Russian law defines as former citizens or descendants of citizens of the Soviet Union or the Russian Empire (this definition also embraces all of Finland and much of Poland). This exercise has already started; see e.g. Russia Reviewing Legality Of Baltics' Independence From Soviet Union viewable at http://www.rferl.org/content/russia-examines-recognition-of-baltic-indep....

As for the wider strategic implications for Russia and the West on a global scale, The Russian Challenge, published this year by The Royal Institute of International Affairs, and viewable at

www.chathamhouse.org/sites/files/chathamhouse/field/field_document/20150... , is recommended reading.

Those who think that the Russians are in Crimea to stay appear to rely primarily on realpolitik and a certain view of history. Kievan Rus' was a loose federation of East Slavic tribes in Europe lasting from the late 9th to the mid-13th Century. At its greatest extent in the mid-11th Century, the federation stretched from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Black Sea in the south. The modern peoples of Belarus, Ukraine, and Russia all claim Kievan Rus' as their cultural ancestors. Before Ukraine became a modern nation, nineteenth-century Russian historians created a model that has Russian history beginning in Kiev. A review of this history is available at http://www.summer.harvard.edu/blog-news-events/conflict-ukraine-historic....

As for realpolitik, the views of the Russian Government and people appear to be firmly supportive of the annexation. Within Crimea, there would appear to be ample support for the annexation, if the results of a March 2014 Crimean referendum are roughly accurate. But this referendum has been widely criticized; see e.g.

www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/mar/17/crimea-referendum-sham-dis... . Yet a Gallup poll taken shortly after the referendum indicates that a large majority of Crimean people considered the referendum results to have been reasonably accurately reflecting most Crimeans' views, and that Crimea's becoming part of Russia will make life better for themselves and their families. According to another survey carried out by Pew Research Center in April 2014, a large majority of Crimean residents in Simferopol, Sevastopol, and Kerch accepted that the referendum was free and fair and that the Ukrainian government should respect the results of the vote.

The Russian Government argues that Khrushchev’s 1954 transfer of Crimea to Ukraine was arbitrary and unjustified. But a majority of Crimeans voted with the rest of Ukraine in the 1991 referendum to leave the Soviet Union. Critics of the 2014 pre-annexation referendum and various post-referendum polls point out that by the spring of 2014, many of the Ukrainians and Tatars had left Crimea, and that an atmosphere of intimidation and fraud prevailed during the staging of the referendum. It appears that the referendum omitted from the choices available to voters a clear preference for remaining in Ukraine.

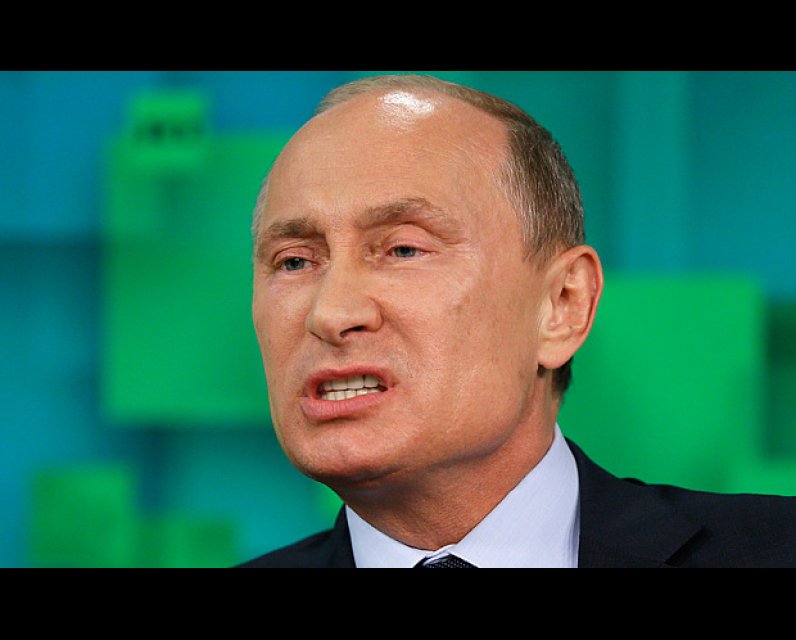

The governments of Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Russia both relied upon constant repetition of the Big Lie to gain political support. Vladimir Putin clearly believes in the value of this tactic, as does much of the Islamist world and as do many of the world’s dictatorships. It seems unlikely that truth, morality, law and reason will prevail over popular mythology in Crimea. Further, the future of Crimea is tied closely to the Russian strategy of perimeter buffer establishment and the perceived military needs of Russia. Russia has a greater direct need for Crimea than has the West. The West’s objective in seeking a return of Crimea to Ukraine is derivative only; the West would like to stop Russian expansion at the earliest possible moment. But Crimea per se is not of great importance to the West, given that Russia had for decades prior to the annexation been able to negotiate with Ukraine a lease to its Sevastopol Black Sea port, as noted above, set to expire in 2042. Without the support of the West, Ukraine alone cannot effectively stand up to Russia.

In this battle of wills, Russia appears to me to have the greater determination to hold on to Crimea and the most to lose if it were to lose Crimea. The West does not provide a solid front – a number of NATO’s European member countries have done little or nothing in the past to support stated NATO political and military objectives. As I see it, the West will have to live with a de facto Russian Crimea, but should properly take measures to see that the Russian expansion disease does not spread.

-- Bob Barrigar, 01 July 2015

Comments

Be the first to comment