Warning message

- Last import of users from Drupal Production environment ran more than 7 days ago. Import users by accessing /admin/config/live-importer/drupal-run

- Last import of nodes from Drupal Production environment ran more than 7 days ago. Import nodes by accessing /admin/config/live-importer/drupal-run

Unpublished Opinions

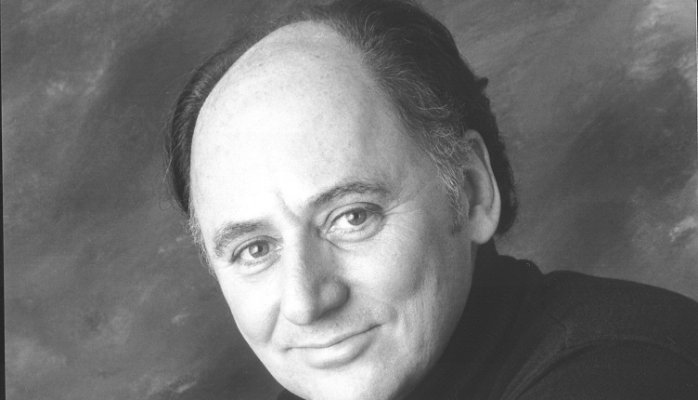

David J. Mitchell has a broad professional background, spanning the private, public and education sectors. From 2009 to 2015 he served as President & CEO of Canada’s Public Policy Forum, an Ottawa-based non-governmental organization dedicated to improving the quality of government through multi-sectoral dialogue.

Previously, he served as Vice-President at three Canadian universities: Queen's, the University of Ottawa and Simon Fraser University. Directing fundraising and external relations at each institution, he achieved notable successes in strategic positioning and fund development.

David served as a Member of the British Columbia Legislature from 1991 to 1996, where he was Opposition House Leader and a watchdog on a broad range of issues including advanced education, resource management, labour relations and governance. He had previously gained experience in parliamentary procedure and legislative processes as Deputy Clerk of the Saskatchewan Legislature.

His significant private sector business experience includes executive positions within western Canadian resource industries, including vice-president of marketing and general manager of industrial relations.

Restoring Trust in Public Institutions: Can Prime Minister Trudeau reverse the trend of political centralization started by his father?

Originally published at PolicyMagazine.ca: http://policymagazine.ca/pdf/16/PolicyMagazineNovemberDecember-2015-Mitchell.pdf

It was one of the more remark-able moments in a long campaign. A poised Justin Trudeau was being interviewed by CBC’s Peter Mansbridge. When asked about criticisms he and others had leveled at the Conservative government for its lack of openness and transparency, he responded with an observation that clearly caught Mansbridge off guard. Acknowledging the trend in recent years towards more control from the Prime Minister’s Office, Trudeau noted, “Actually it can be traced as far back as my father, who kicked it off in the first place...”

A surprised Mansbridge was obviously expecting a partisan attack on Stephen Harper, not a critique of Pierre Elliot Trudeau, the Liberal leader’s own father. But the younger Trudeau seemed to relish the moment, adding:

“...I actually quite like the symmetry of me being the one who’d end that. My father had a particular way of doing things; I have a different way, and his was suited to his time and mine is suited to my time. I believe that we need to trust Canadians. I believe that it’s not just about restoring Canadians’ trust in government by demonstrating trust towards them, I think we get better public policy when it’s done openly and transparently...”

In addition to providing an unexpected rebuke of his father’s approach to politics and governing, the interview also suggested what Justin Trudeau viewed as a key challenge for Canadian democracy: restoring trust in public institutions.

How to achieve this, and whether it’s actually possible, now become critically important questions for the new government in Ottawa. Expectations are high—and so are the hurdles ahead. Nevertheless, the Liberal Party’s election platform and Trudeau’s public statements provide clues to how these governance challenges might be approached.

The key will be whether our new prime minister can buck the seemingly irreversible trend of centralization of authority, which, as he acknowledged, his father began almost half a century ago.

On the subject of governance, these include: electoral reform; a commitment to evidence-based policy; establishing a chief science officer; more free votes in the House of Commons; not resorting to omnibus bills designed to prevent parliament from doing its job; engaging young Canadians; espousing more openness and transparency; and that old chestnut, Senate reform.

While the list of specific—and some not-so-specific—promises is broad and impressive, perhaps as important is the tone and anticipated management style of the new administration. And here the contrast with the previous government appears to be quite dramatic. Prime Minister Trudeau has promised a more open, accessible and collegial approach to governance. Will he be able to deliver and sustain this?

The key will be whether our new prime minister can buck the seemingly irreversible trend of centralization of authority, which, as he acknowledged, his father began almost half a century ago. This is not unique to Canada; in fact, it’s evident in most western democracies. Globalization, technology and social media have increased the ambitions of governments trying to respond quickly and decisively to emerging issues. Generally, this has resulted in much more centralized control.

In Canada, while this tendency has been reinforced decade upon decade, it’s widely agreed that political power in Ottawa has become increasingly concentrated in recent years. And although Justin Trudeau mused about the controlling instincts of his father, his more immediate reference point is obviously the government of his predecessor, Stephen Harper, broadly known for taking the centralization of authority to unprecedented levels.

When a powerful PMO appropriates all strategy, management and decision-making unto itself, there is an inevitable cost. When a prime minister and his political staff attempt to control and run not only the PMO but also cabinet, Parliament and the public service, there are consequences—many of them unintended. And when important public institutions such as these are consistently undermined, our system of governance suffers a loss of confidence and public trust. This can’t be easily reversed.

On election night, Justin Trudeau invoked the spirit of another Canadian prime minister from a century ago, Wilfred Laurier. He referred to his “sunny ways”—one of Laurier’s political trademarks. Today, Prime Minister Trudeau’s own optimism and positive attitude should not be underestimated in setting a new and different approach in our capital. However, there are three specific areas that require his administration’s focused attention in order to re-energize the Westminster model of governance in Canada.

1. Restore cabinet government. The prime minister has already signalled that he is unafraid to surround himself with smart, competent women and men. Clearly, his intention is to provide a more collegial style of leadership, delegating responsibility and accountability to his ministers. But will cabinet actually meet on a regular basis and act as a decision-making body? This would certainly be at odds with recent practice. Indeed, the description of cabinet as a mere focus group for the PM has often seemed apt.

Justin Trudeau’s determination to keep his cabinet small and gender-balanced represents a clear path towards the “real change” of his election manifesto. Will he be able to sustain these changes? And will we see an actual return to cabinet government, with ministers providing a counterbalance to unrestricted prime ministerial authority?

Here’s an indicator that we might look for: will ministers appoint their own political advisers? Under the Conservative government all political staff were appointed by and reported to the PMO.

2. Empower parliamentary committees. Parliament has suffered greatly in recent years, with the combination of expense scandals in the Senate and the atmosphere of a permanent election campaign in the House of Commons. Reforming question period and allowing for more free votes, as promised by the Liberals, would be positive steps. However, the change that holds the greatest potential to improve the relevance of this flagging institution would be providing greater independence and authority to parliamentary committees.

To be fair, the Liberal election platform addresses this issue by proposing that committee chairs be elected by a secret ballot of all MPs, the same way the Speaker is now elected. This would allow less interference and direction from PMO. However, we should go much further.

Committee chairs and members should be elected for the four-year life of a parliament, providing better and more independent scrutiny of the executive branch of government. And committees should be provided with more resources in order to reach out effectively to Canadians, engaging them not only on the issues of the day, but also on issues of medium to long-term policies.

An indicator of success: the position of committee chair will be almost as coveted as a cabinet post (often the case in the United Kingdom).

3. Rethink the public service. Canada has long been respected for the professionalism of its permanent, non-partisan public service. However, during recent years its reputation has been diminished. The relationship between public servants and political staff has often been unclear and sometimes uncomfortable. Public servants have also been blamed when things go wrong, even when the directions being followed clearly emanated from political levels.

The public service is an important institution providing a comparative advantage for our country. No government can long afford a demoralized or demotivated bureaucracy. However, some clarity and commitment to its essential role is required, especially with respect to delivery of services and policy development. Ideally, this would come directly from the prime minister and be codified in the form of a charter or by legislation.

The public service should become recognized not only as the largest employer in Canada but as the employer of choice for a new generation of emerging leaders.

The new government led by Prime Minister Trudeau has already established some ambitious goals and new policy directions. The success of any government can be judged by how well its priorities are aligned with the desires of citizens and the tenor of the times. Usually, it’s only in retrospect, years afterward, that we can take stock and gain such a perspective. Critics, supporters and historians will therefore need to bide their time if they wish to accurately assess the successes and failures of the Conservative government led by Stephen Harper.

As for the new Liberal administration in Ottawa, still enjoying the honeymoon euphoria of victory and marching now with confidence into its first 100 days in office, the joys of success and inevitable failures both lie ahead. But it’s interesting to speculate on how the political style and managerial approach of Justin Trudeau might one day be judged. If he achieves even a modicum of success in restoring trust in important institutions of governance such as cabinet, parliament and the public service, he will have defied the dominant centralizing tendencies that started in Canada with his father.

Contributing Writer David Mitchell

is an author, political historian and

public policy consultant.

david@davidjmitchell.ca

Comments

Be the first to comment