Warning message

- Last import of users from Drupal Production environment ran more than 7 days ago. Import users by accessing /admin/config/live-importer/drupal-run

- Last import of nodes from Drupal Production environment ran more than 7 days ago. Import nodes by accessing /admin/config/live-importer/drupal-run

Unpublished Opinions

2010-Present Green Party shadow cabinet critic for Small Business and Entrepreneurship.

2015 Green Party Candidate for Nepean

2011 Green Party Candidate for Nepean--Carleton

Lessons we can learn from German Greens

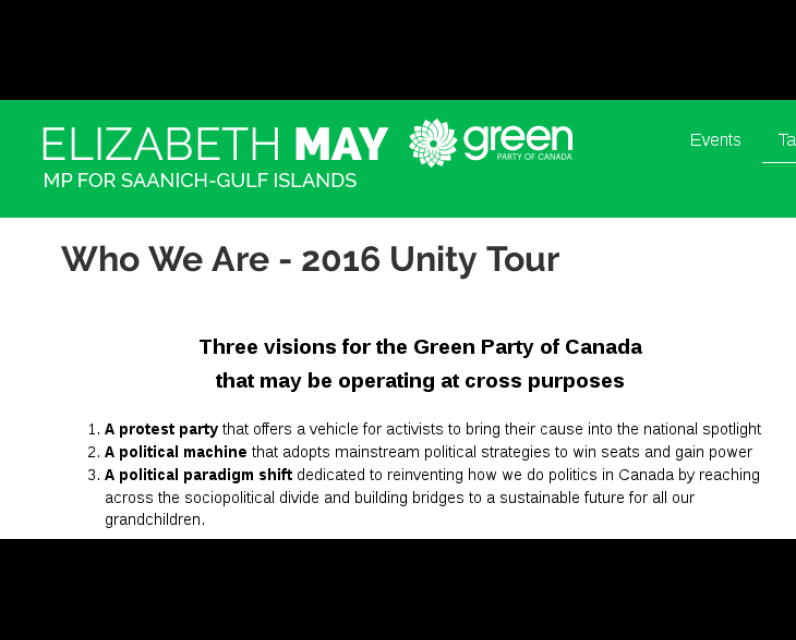

The members of Green Party of Canada passed a very contravercial policy this summer tacitly endorsing the anti-Israeli BDS movement (Jean-Luc Cooke was one of the most vocal opponents).

The pro-BDS side has dug in and many members of the party who joined for other reasons are left wondering "who we are".

The global perspective from our big brothers in Europe (who have almost idential membership numbers per-capita) have important lessons.

In 1980, at the foundation congress of the German Greens, the famous four pillars of the Green Party were first proclaimed:

- Social Justice

- Ecological Wisdom

- Grass-roots Democracy

- Non-violence

Greens have come a long way since then.

Representative democracy demands that people come together. To do that in confidence requires a high level of certainty that the policies a party puts forward, represent the full collective wisdom of the party. All this requires a framework of active and equitable member participation.

Our current debate around what happened at last summer’s convention represents a natural maturing that is fraught with danger but offers great rewards. Other political parties including the German Greens, who have successfully been in government as part of a coalition have found themselves going through this same evolutionary process.

Like us, they can trace their roots back to the time when they were a protest movement. There was slim hope of gaining power or even winning seats to affect votes in the house. Wrapping the protest into a political party, gave it more legitimacy and more exposure, it was hoped, to the media.

Protests are a critical component to keeping a free society free. They spark debate and organize communities around change. They can inform and inspire. Protest movements by their very nature are unpredictable and in fierce opposition to the decision makers that manage our national affairs. That’s what makes them protests.

As a political party matures, and especially once it wins seats in the house, it quickly learns that politics are not about protest. Politics are about gaining influence. Politics require compromise, negotiation and bridge building. Why? because to get elected you have to represent more than yourself, more than a small sector of society, more than a single cause. Before citizens will place their vote in your care they must feel certain that you are able to represent them on a range of issues that matter to them.

In the 1970s Chancellor Brandt was able to absorb the needs of protest movements in Germany, much like Pierre Trudeau did here in Canada. His social democratic successor Schmidt, however, had an explicitly non-green agenda, helping German Greens to gain a foothold as a political party. But then their first successes and early responsibility in regional governments (like Hessen in 1985 with Joschka Fischer as Vice-Governor) helped the greens to slowly peel off radical positions at the periphery of the party. In the process they have lost many (even prominent) members over the years, most of which have left, accusing the party of becoming too established.

Green issues in Germany have always included peace and nuclear disarmament. So while their focus remained on global issues and foreign affairs, German Greens continued to gather governing experience at the Provincial/State level. As a party that had learned for years about budget planning and changing environmental law, they then entered a seven year period (until 2005) in which they learned about tough decisions on the federal level, like compromises about a nuclear phase out or military engagement in former Yugoslavia. This built a stronger core but temporarily cost them 25% of their membership.

Ever since 2005 they have, again, redefined their role as competent leaders in all environmental issues, pushing the energy revolution and widening their competence in the fields of consumer rights, civil rights and education. As the Social Democrats weakened over the years, the left and the right got stronger as did the Greens. It became obvious that Greens had to find their strength and will to search for power beyond their "natural partner", the Social Democrats. This ongoing process is far from being easy but German Greens have evolved to become an established party, campaigning for power and responsibility.

Today The Greens are in power in 10 out of 16 States/Provinces. Soon the city-State of Berlin will follow. There are about seven different types of coalitions: In Baden-Württemberg there is a Green governor (30% of the popular vote) in a coalition with the Conservatives - in a conservative State. The other coalitions span the political spectrum with Greens taking the role of forward looking progressives that protect mainstream parties from having to form coalitions with extremist groups to form a majority. Now about 2/3rds of the Environment Ministers at the State/Provincial level are Greens.

German Greens have developed a system of regional and proportional representation within their party to insure not only that policies brought to the floor of the convention represent the broader membership but also that those who vote at convention do. To be credible the entire policy development process has to be defensible not only to party insiders but to the voting pubic at large. Their process includes regional meetings to elect delegates at the ratio of 1 for every 50 members, that are then encouraged to go to convention. Funding for this is raised locally.

Their process also allows for some votes to be determined by the full membership and provides certain autonomy for local bodies and even wings of the party to organize themselves. There are instruments in their statutes that allow a critical mass for different levels of intervention. We can learn from their experience and develop a process designed for Canadian Greens.

The values of representative democracy and proportional representation are the underpinning of their system. And rightfully so since their political framework of Consensus Based Governance makes it possible for them to currently have over 60 seats in the house.

They also have experience with the dynamic change that takes place once MPs get elected and a sizeable caucus is formed. Each MP has a parliamentary staff and together they represent a formidable influence within the party. It was a rocky road that took many years but it resulted in a strong presence in parliament. Yes, Greens have come a long way. But Social Justice, Ecological Wisdom, Grass-roots Democracy and Non-violence are still core principles that unite us.

The German Green experience is not a blueprint for Canadian Greens. Rather it is a beacon of hope. An assurance that there is a path from here to there. That the growing pains we are currently experiencing are quite normal and part of a maturing process that is not unique to us. Other young parties, even here in Canada, have gone through similar phases. Each has handled it differently. But only those that have handled it successfully have survived.

It’s time to embark on this process. With Electoral Reform on the horizon, this is our chance to demonstrate our commitment to responsible governance, both inside and outside the Green Party of Canada.

Thomas Teuwen - party member from Saanich Gulf Islands

Comments

Be the first to comment