×

Warning message

- Last import of users from Drupal Production environment ran more than 7 days ago. Import users by accessing /admin/config/live-importer/drupal-run

- Last import of nodes from Drupal Production environment ran more than 7 days ago. Import nodes by accessing /admin/config/live-importer/drupal-run

Unpublished Opinions

smiths falls, Ontario

About the author

Advocates for family preservation against unwarranted intervention by government funded non profit agencies and is a growing union for families and other advocates speaking out against the children's aid society's funding strategies and current corrupt practices to achieve the society's funding goals.

MAYBE IT'S TIME FOR THE GOVERNMENT TO ACCESS DIFFERENT CHILD WELFARE EXPERTS?

November 16, 2019

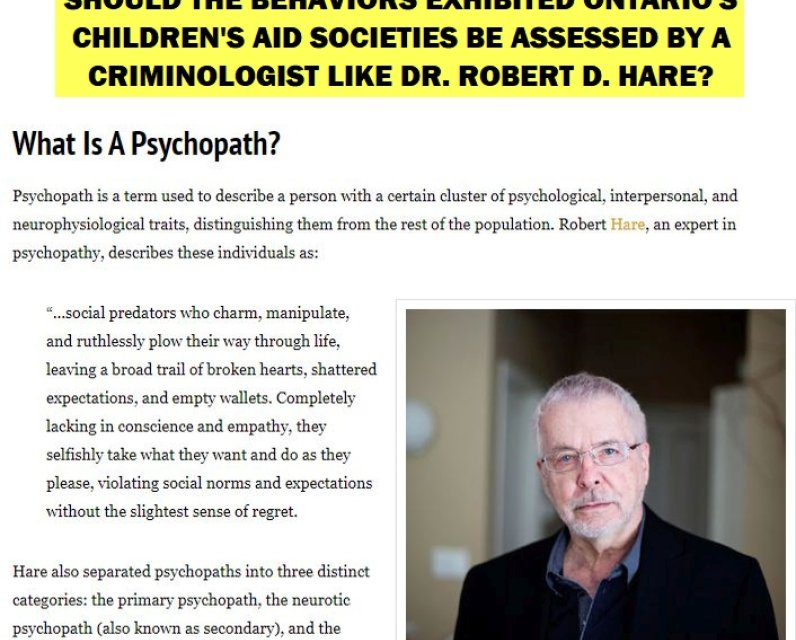

SHOULD THE BEHAVIORS EXHIBITED ONTARIO'S CHILDREN'S AID SOCIETIES BE ASSESSED BY A CRIMINOLOGIST LIKE DR. ROBERT D. HARE?

Criminology is an area of sociology that focuses on the study of crimes and their causes, effects, and social impact. A criminologist's job responsibilities involve analyzing data to determine why the crime was committed and to find ways to predict, deter, and prevent further criminal behavior.

See: Robert D. Hare, C.M. (born 1934 in Calgary, Alberta, Canada) is a researcher in the field of criminal psychology. He developed the Hare Psychopathy Checklist (PCL-Revised), used to assess cases of psychopathy. Hare advises the FBI's Child Abduction and Serial Murder Investigative Resources Center (CASMIRC) and consults for various British and North American prison services.

Hare wrote a popular science bestseller published in 1993 entitled Without Conscience: The Disturbing World of the Psychopaths Among Us (reissued 1999).

He describes psychopaths as 'social predators', while pointing out that most don't commit murder. One philosophical review described it as having a high moral tone yet tending towards sensationalism and graphic anecdotes, and as providing a useful summary of the assessment of psychopathy but ultimately avoiding the difficult questions regarding internal contradictions in the concept or how it should be classified.

Hare received his Ph.D. in experimental psychology at University of Western Ontario (1963). He is professor emeritus of the University of British Columbia where his studies center on psychopathology and psychophysiology. He was invested as a Member of the Order of Canada on December 30, 2010.

Hare's research on the causes of psychopathy focused initially on whether such persons show abnormal patterns of anticipation or response (such as low levels of anxiety or high impulsiveness) to aversive stimuli ('punishments' such as mild but painful electric shocks) or pleasant stimuli ('rewards', such as a slide of a naked body). Further, following Cleckley, Hare investigated whether the fundamental underlying pathology is a semantic affective deficit - an inability to understand or experience the full emotional meaning of life events. While establishing a range of idiosyncrasies in linguistic and affective processing under certain conditions, the research program has not confirmed a common pathology of psychopathy. Hare's contention that the pathology is likely due in large part to an inherited or 'hard wired' deficit in cerebral brain function remains speculative.[10]

Hare has defined sociopathy as a separate condition to psychopathy, as caused by growing up in an antisocial or criminal subculture rather than there being a basic lack of social emotion or moral reasoning. He has also regarded the DSM-IV diagnosis of Antisocial Personality Disorder as separate to his concept of psychopathy, as it did not list the same underlying personality traits. He suggests that ASPD would cover several times more people than psychopathy, and that while the prevalence of sociopathy is not known it would likely cover considerably more people than ASPD.[11]

Assessment tools

Frustrated by a lack of agreed definitions or rating systems of psychopathy, including at a ten-day international North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) conference in France in 1975, Hare began developing a Psychopathy Checklist. Produced for initial circulation in 1980, the same year that the DSM changed its diagnosis of sociopathic personality to Antisocial Personality Disorder, it was based largely on the list of traits advanced by Cleckley, with whom Hare corresponded over the years. Hare redrafted the checklist in 1985 following Cleckley's death in 1984, renaming it the Hare Psychopathy Checklist Revised (PCL-R). It was finalised as a first edition in 1991, when it was also made available to the criminal justice system, which Hare says he did despite concerns that it was not designed for use outside of controlled experimental research.[12] It was updated with extra data in a 2nd edition in 2003.

The PCL-R was reviewed in Buros Mental Measurements Yearbook (1995), as being the "state of the art" both clinically and in research use. In 2005, the Buros Mental Measurements Yearbook review listed the PCL-R as "a reliable and effective instrument for the measurement of psychopathy" and is considered the 'gold standard' for measurement of psychopathy. However, it is also criticised.[13]

Hare has accused the DSM's ASPD diagnosis of 'drifting' from clinical tradition, but his own checklist has been accused of in reality being closer to the concept of criminologists William and Joan McCord than that of Cleckley; Hare himself, while noting his promotion of Cleckley's work for four decades, has distanced himself somewhat from Cleckley's work.[14][15][16]

Hare is also co-author of derivatives of the PCL: the Psychopathy Checklist: Screening Version (PCL:SV)[17] (still requires a clinical interview and review of records by a trained clinician), the P-Scan (P for psychopathy, a screening questionnaire for non-clinicians to detect possible psychopathy), the Psychopathy Checklist: Youth Version (PCL:YV) (to assess youth and children exhibiting early signs of psychopathy), and the Antisocial Process Screening Device (originally the Psychopathy Screening Device; a questionnaire for parents/staff to fill out on youth, or in a version developed by others, for youth to fill out as self-report).[18] Hare is also a co-author of the Guidelines for a Psychopathy Treatment Program. He has also co-developed the 'B-Scan' questionnaires for people to rate psychopathy traits in others in the workplace.[19]

:::

Workers at Quaker Road group home near Oakwood where fire killed two people Feb. 24 speak out.

The caregivers of Quaker Rd. don’t scare easily. They bear the wounds of their commitment without complaint — a bald spot where hair was ripped out, scars where bites removed chunks of flesh, more punches and kicks to the head than anyone should ever have to count.

The last thing they want is to portray the children they cared for in two group homes, on the same rural property near Oakwood, about 58 kilometres west of Peterborough, as monsters. The cruelty, they say, is in a child protection system that warehouses its most vulnerable kids while giving their caregivers almost no support.

Part of the problem lies in a striking fact: Ontario has no minimum education requirement for group home caregivers. Anyone can be hired as long as they pass a police record check, review a ministry manual on policies and procedures, and complete an eight-hour course on physical restraints, managing aggressive behaviour, and crisis intervention.

The lack of professional standards has been noted in numerous reports during the past decade that have described Ontario's residential care system as dysfunctional. The most recent, by the 2016 expert panel, lambasted a system where the government can't even keep track of kids in residential care, let alone ensure they're being treated properly.

The Ministry of Children and Youth Services spends $1.5 billion annually on a child protection system that serves some 14,000 kids taken from abusive or neglectful parents and helps many more in their own homes.

In 2016-17, children's aid societies spent $231.2 million of that money on "outside paid resources," the term usually used for group homes and foster homes run, for profit, by private companies.

:::

Shedding light on the troubles facing kids in group homes.

:::

Why are children in CAS care described like criminals?

:::

Toronto group homes turning outbursts from kids into matters for police

:::

A CHILD IN CARE IS A CHILD AT RISK.

Ontario’s child protection system fails children, again.

By Star Editorial Board Wed., Sept. 26, 2018 .

Children should, at the very least, survive the attempts of Ontario’s child protection system to help them.

What an incredibly low bar that is, Ontario’s child advocate noted. And how shocking that, yet again, Ontario has failed to meet it.

:::

Teen’s death in unlicensed Oshawa group home raises questions about secrecy surrounding kids in care. NEWS Dec 10, 2015.

DURHAM -- On a late afternoon in April, Justin Sangiuliano put on his helmet and gloves to go for a bicycle ride.

But staff at the unlicensed Oshawa group home where the 17-year-old developmentally disabled teen lived were planning to take him fishing instead. They locked the bicycle shed to be sure the energetic six-footer got the message.

Justin was furious. He stormed around the home, swinging his fists until staff grabbed his arms to restrain him. Kicking and screaming — and still in the clutches of two staff members — the teen fell to the living room floor, where he reportedly rubbed his face back and forth on the carpet until his forehead, chin and cheeks were raw.

Some time later, he stopped struggling and staff released him. But Justin never got up. He was rushed to Lakeridge Health Oshawa and arrived without a heartbeat, according to a serious occurrence report filed by Enterphase Child and Family Services, the private company that runs the group home.

:::

2014: A Toronto Star investigation has found Ontario’s most vulnerable children in the care of an unaccountable and non-transparent protection system. It keeps them in the shadows, far beyond what is needed to protect their identities.

There is a child in the Ontario government’s care who has changed homes 88 times. He or she is between 10 and 15 years old.

Senior government officials describe The Case of the Incredible Number of Moves as a “totally unacceptable outlier.”

Yet they don’t know what is being done to ensure the 88th move is the child’s last. The local children’s aid society is required to have a “plan of care” for each child. Whatever it is, it’s clearly not working.

The case was noted in government-mandated surveys obtained by the Star. The reports show three other teens changing homes more than 60 times.

Getting more details on how many times children change homes while in care is a murky business. A child welfare commission appointed by the government noted in 2012 that Ontario’s 46 children’s aid societies don’t agree on how to count or record such moves.

Child welfare system lacks accountability and transparency, with services for vulnerable children described as “fragmented, confused”

The commission looked at two groups of children who had spent at least 36 months in care. About 20 per cent of them changed homes more than three times. The Star obtained the commission’s numbers through a freedom-of-information request.

The government, while expressing concern, has done little to ensure more stable environments for children who experience multiple moves once taken from their parents. And it has not publicized data that would flag the issue.

Tragic examples of children dying while in contact with a CAS — including a case where a child-protection worker was charged with criminal negligence — triggered province-wide alarm in the late 1990s, fuelled by coroners’ inquests and media stories.

2016: “There are lots of kids in group homes all over Ontario and they are not doing well — and everybody knows it,” says Kiaras Gharabaghi, a member of a government-appointed panel that examined the residential care system.

2018: “We need to do more to make sure that children care are safe and cared for. When a child dies, someone (is held?) responsible,” Children, Community and Social Services minister Lisa MacLeod added.

“From the CASs to group and foster homes to my ministry, we all bear (some?) responsibility,” MacLeod said, referring to Ontario’s 49 children’s aid societies. “And I want to assure the house that, as the new minister, the buck stops with me and I will take action before I'm held accountable.”

Between 2014\15 the Ontario children's aid society claim to have spent $467.9 million dollars providing protective services that doesn't seem to extent to the 90 to 120 children that die in Ontario's foster care and group homes that are overseen and funded by the CAS.

In a National Post feature article in June 2009, Kevin Libin portrayed an industry in which abuses are all too common. One source, a professor of social work, claims that a shocking 15%-20% of children under CAS oversight suffer injury or neglect.

Several CAS insiders whom Libin interviewed regard the situation as systemically hopeless.

A clinical psychologist with decades of experience advocating for children said, “I would love to just demolish the system and start from scratch again.”

Barbara Kay: The problem with Children’s Aid Societies

National Post - Wednesday February 27th, 2013.

:::

Nearly half of children in Crown care are medicated.

Psychotropic drugs are being prescribed to nearly half the Crown wards in a sample of Ontario children's aid societies, kindling fears that the agencies are overusing medication with the province's most vulnerable children.

Ontario researchers have found that not only were psychotropic drugs prescribed to a clear majority of the current and former wards interviewed, but most were diagnosed with mental-health disorders by a family doctor, never visited a child psychiatrist or another doctor for a second opinion, and doubted the accuracy of their diagnosis.

A Toronto Star investigation has found Ontario’s most vulnerable children in the care of an unaccountable and non-transparent protection system. It keeps them in the shadows, far beyond what is needed to protect their identities.

“When people are invisible, bad things happen,” says Irwin Elman, Ontario’s now former and last advocate for children and youth with the closure of the Office.

A disturbing number, the network's research director, Yolanda Lambe, added, have traded the child-welfare system for a life on the street.

"A lot of people are using drugs now," she said. "There's a lot of homeless young people who have been medicated quite heavily."

In Ontario the CAS has turned themselves into a multi-billion dollar private corporation using any excuse to compel parents into submitting to fake drug testing to justify removing children or keeping files open keeping that government funding flowing.

All the while they've taking the thousands of children to specific CAS approved doctors who are all to happy to prescribe medication based on the workers assessments of the child's condition.. That's why there are no follow ups with qualified medical and psychiatric doctors and not because the CAS lack the funding, staff or attention span to care properly for the children.

Marti McKay is a Toronto child psychologist was hired by a CAS to assess the grandparents' capacity as guardians only to discover a child so chemically altered that his real character was clouded by the side effects of adult doses of drugs.

"There are lots of other kids like that," said Dr. McKay, one of the experts on the government panel. "If you look at the group homes, it's close to 100 per cent of the kids who are on not just one drug, but on drug cocktails with multiple diagnoses.

"There are too many kids being diagnosed with ... a whole range of disorders that are way out of proportion to the normal population. ... It's just not reasonable to think the children in care would have such overrepresentation in these rather obscure disorders."

According to documents obtained by The Globe and Mail under Ontario's Freedom of Information Act, 47 per cent of the Crown wards - children in permanent CAS care - at five randomly picked agencies were prescribed psychotropics last year to treat depression, attention deficit disorder, anxiety and other mental-health problems. And, the wards are diagnosed and medicated far more often than are children in the general population.

"Use of 'behaviour-altering' drugs widespread in foster, group homes."

Almost half of children and youth in foster and group home care aged 5 to 17 — 48.6 per cent — are on drugs, such as Ritalin, tranquilizers and anticonvulsants, according to a yearly survey conducted for the provincial government and the Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies (OACAS). At ages 16 and 17, fully 57 per cent are on these medications.

In group homes, the figure is even higher — an average of 64 per cent of children and youth are taking behaviour-altering drugs. For 10- to 15-year-olds, the number is a staggering 74 per cent.

:::

What’s worse is that the number of children prescribed dangerous drugs is on the rise. Doctors seem to prescribe medication without being concerned with the side-effects.

Worldwide, 17 million children, some as young as five years old, are given a variety of different prescription drugs, including psychiatric drugs that are dangerous enough that regulatory agencies in Europe, Australia, and the US have issued warnings on the side effects that include suicidal thoughts and aggressive behavior.

According to Fight For Kids, an organization that “educates parents worldwide on the facts about today’s widespread practice of labeling children mentally ill and drugging them with heavy, mind-altering, psychiatric drugs,” says over 10 million children in the US are prescribed addictive stimulants, antidepressants and other psychotropic (mind-altering) drugs for alleged educational and behavioral problems.

In fact, according to Foundation for a Drug-Free World, every day, 2,500 youth (12 to 17) will abuse a prescription pain reliever for the first time (4). Even more frightening, prescription medications like depressants, opioids and antidepressants cause more overdose deaths (45 percent) than illicit drugs like cocaine, heroin, methamphetamines and amphetamines (39 percent) combined. Worldwide, prescription drugs are the 4th leading cause of death.

:::

Standards of Care for the Administration of Psychotropic Medications to Children and Youth Living in Licensed Residential Settings.

Summary of Recommendations of the Ontario Expert Panel February 2009.

:::

PARENTS RIGHTS WERE RIPPED OUT BY THE ROOTS.

“Harmful Impacts” is the title of the Motherisk commission's report written by the Honourable Judith C. Beaman after two years of study. After reading it, “harmful” seems almost to be putting it lightly. Out of the over 16 000 tests (though that number has been reported as high as 35 000 tests) the commission only examined 56 cases of the flawed Motherisk tests, administered by the Motherisk lab between 2005 and 2015 and were determined to have a “substantial impact” on the decisions of child protection agencies to keep files open or led to children being permanently removed from their families.

WHAT ARE THE HARMFUL IMPACTS?

Separating kids from parents a 'textbook strategy' of domestic abuse, experts say — and causes irreversible, lifelong damage even when there is no other choice.

“Being separated from parents or having inconsistent living conditions for long periods of time can create changes in thoughts and behavior patterns, and an increase in challenging behavior and stress-related physical symptoms,” such as sleep difficulty, nightmares, flashbacks, crying, and yelling says Amy van Schagen - California State University.

The Science Is Unequivocal: Separating Families Is Harmful to Children Even When There Is No Other Choice.

In news stories and opinion pieces, psychological scientists are sharing evidence-based insight from decades of research demonstrating the harmful effects of separating parents and children.

In an op-ed in USA Today, Roberta Michnick Golinkoff (University of Delaware), Mary Dozier (University of Delaware), and Kathy Hirsh-Pasek (Temple University) write:

“Years of research are clear: Children need their parents to feel secure in the world, to explore and learn, and to grow strong emotionally.”

In a Washington Post op-ed, James Coan (University of Virginia) says:

“As a clinical psychologist and neuroscientist at the University of Virginia, I study how the brain transforms social connection into better mental and physical health. My research suggests that maintaining close ties to trusted loved ones is a vital buffer against the external stressors we all face. But not being an expert on how this affects children, I recently invited five internationally recognized developmental scientists to chat with me about the matter on a science podcast I host. As we discussed the border policy’s effect on the children ensnared by it, even I was surprised to learn just how damaging it is likely to be.”

Mia Smith-Bynum (University of Maryland) is quoted in The Cut:

“The science leads to the conclusion that the deprivation of caregiving produces a form of extreme suffering in children. Being separated from a parent isn’t just a trauma — it breaks the relationship that helps children cope with other traumas.

Forceful separation is particularly damaging, explains clinical psychologist Mia Smith-Bynum, a professor of family science at the University of Maryland, when parents feel there’s nothing in their power that can be done to get their child back.

For all the dislocation, strangeness and pain of being separated forcibly from parents, many children can and do recover, said Mary Dozier, a professor of child development at the University of Delaware. “Not all of them — some kids never recover,” Dr. Dozier said. “But I’ve been amazed at how well kids can do after institutionalization if they’re able to have responsive and nurturing care afterward.”

The effects of that harm may evolve over time, says Antonio Puente, a professor of psychology at the University of North Carolina, Wilmington who specializes in cultural neuropsychology. What may begin as acute emotional distress could reemerge later in life as PTSD, behavioral issues and other signs of lasting neuropsychological damage, he says.

“A parent is really in many ways an extension of the child’s biology as that child is developing,” Tottenham said. “That adult who’s routinely been there provides this enormous stress-buffering effect on a child’s brain at a time when we haven’t yet developed that for ourselves. They’re really one organism, in a way.” When the reliable buffering and guidance of a parent is suddenly withdrawn, the riot of learning that molds and shapes the brain can be short-circuited, she said.

In a story from the BBC, Jack Shonkoff (Harvard University) discusses evidence related to long-term impacts:

Jack P Shonkoff, director of the Harvard University Center on the Developing Child, says it is incorrect to assume that some of the youngest children removed from their parents’ care will be too young to remember and therefore relatively unharmed. “When that stress system stays activated for a significant period of time, it can have a wear and tear effect biologically.

:::

“It is stunning to me how these children... are rendered invisible while they are alive and invisible in their death,” said Irwin Elman, Ontario’s advocate for children and youth. Between 90 and 120 children and youth connected to children’s aid die every year.

“When people are invisible, bad things happen,” says Irwin Elman, the Provincial Advocate for Children and Youth.

Why did 90 children die?

Why did a lot more ie after that and why is undetermined cause the leading cause of death for children in care?

:::

Neglect is one of the most common child protection concerns in Ontario: Q & A with OACAS’ CEO

Neglect is one of the most common child protection concerns in Ontario.

Mary Ballantyne, CEO of the Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies, discusses how Children’s Aid Societies help families dealing with this issue.

How is neglect a form of child abuse?

A child who is neglected is consistently not having their vital needs met. That could mean poor nutrition, lack of attention to hygiene, and so on. From a child welfare perspective, neglect is a concern because it ultimately affects a child’s ability to thrive. With very young children, neglect is obviously a real, immediate risk. Inadequate feeding can be life threatening, and lack of attention to hygiene can lead to serious illness. As children mature, neglect might not be a matter of life and death, but it does affect how a child manages day-to-day. A hungry child will struggle in school and can be bullied and ridiculed by peers because of poor hygiene. As children enter adolescence, we start seeing the impacts of neglect on their behaviour, including lower self-esteem and an inability to engage in school because they lack the confidence and skills.

How does child welfare help children who have been neglected?

One of the biggest challenges for a child welfare worker is determining what is at the root of the neglect. Is it that the parent lacks the skills to take care of their child? Is it an addiction or a mental health issue? Poverty can also mean that a parent can’t adequately provide for their child, because there are too many competing needs for the limited resources they do have.

So how will child welfare responses differ according to these different situations?

If it’s a parenting skills issue, a child welfare worker will work with the parent or connect the parent with the resources they need to learn those skills. With an addiction or a mental health issue, the parent can enter a treatment program. If it’s poverty that’s contributing to neglect, the worker can advocate on the family’s behalf to get them the resources they need. In some cases it’s a combination of all those approaches. It’s important to understand that poverty is recognized as a risk factor in abuse and neglect cases, but it does not cause abuse and neglect. Children are also neglected in families with higher socio-economic status.

Concrete interventions can often really help some families. It can be extremely hard for a family living in close quarters where the building is falling apart and unsafe. If a child welfare worker can find them a reasonable place to live, where they feel pride, neglect can be reduced. Similarly, alleviating daily stresses by providing transportation or daycare allows a parent to focus more on child rearing. When parents feel good about themselves, it makes them better parents.

Is this a role that child welfare should be taking on?

This is a role that child welfare has played for decades, but it’s probably not well understood as an important form of intervention. The Ontario Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect shows that 89% of child welfare’s work involves children and families struggling with chronic needs such as poverty, trauma, mental health, and addictions.* Child welfare plays an important role in linking struggling families to the many vital programs available in their community. In-home, hands-on support is crucial: people learn how to be good parents while receiving support for themselves and their child along the way.

A recent CAS study using data from the Ontario Incidence Study shows that poverty is a correlated to the disproportionate number of Indigenous and African Canadian children taken into care. Does child welfare’s work with children experiencing neglect unfairly impact families living in poverty?

We know that poverty is racialized in Ontario and Canada – the rates of Indigenous and African Canadian families living in poverty is disturbingly high. Because we work with children experiencing neglect, and poverty can often look like neglect, we realize that this might be a contributing factor to these communities being overrepresented.

With the support of the Government, we’ve been consulting on the issue of overrepresentation with African Canadian communities. The release of the One Vision, One Voice Practice Framework: Changing the Ontario Welfare System to Better Serve African Canadians is an important step on this journey of understanding.

What role can the community play in helping children who are neglected?

The community has a huge role to play. Knowing that someone in your community is struggling, you can ask yourself how you can help them. Offering to take care of your neighbour’s kids after school, sharing a meal, or simply listening are important ways to be part of the solution.

Another important thing for people in the community to do if they believe that a child is being abused or neglected is to call Children’s Aid. Their call can lead to an offer of support to someone who can’t help themselves.

* A 25 Year Perspective on Child Welfare Services in Ontario and Canada, Nico Trocmé, McGill University

On September 29, 2015 / Child Abuse Prevention, Children, Children's Aid Societies, Featured, Youth

:::

A scathing report from Ontario’s coroner presses the provincial government to reform a child protection system that “repeatedly failed” 12 youths who died while in care.

“Change is necessary, and the need is urgent,” said the report, written by a panel of experts appointed by chief coroner Dirk Huyer last November to examine the spike of deaths between January 2014 and July 2017.

The 86-page report found that the12 youths — eight of whom were Indigenous — were all in the care of Ontario’s child protection system and living in unsafe homes when they died.

The report describes a fragmented system with no means of monitoring quality of care, where ministry oversight is inadequate, caregivers lack training, and children are poorly supervised. Vulnerable children are being warehoused and forgotten.

The expert panel convened by Ontario chief coroner Dirk Huyer to avoid another very "embarrassing" public inquest for our extremely secretive child welfare officials - the expert panel (leaving out nothing) found a litany of other problems, including:

Evidence that some of the youths were "at risk of and/or engaged in human trafficking."

A lack of communication between child welfare societies.

Poor case file management.

An "absence" of quality care in residential placements.

Eleven of the young people ranged in age from 11 to 18. The exact age of one youth when she died wasn't clear in the report.

The inquest into Jeffrey Baldwin's death was supposed to shed light on the child welfare system and prevent more needless child deaths. Baldwin's inquest jury made 103 recommendations. Sep 06, 2013.

Nearly six months after the inquest into the death of Katelynn Sampson began, jurors delivered another 173 recommendations. APRIL 29, 2016.

276 OFFICIAL REASONS FOR CONCERN ABOUT CHILDREN IN CARE.

:::

2018: Office of the Chief Coroner

"Safe With Intervention?"

The Report of the Expert Panel on the Deaths of Children and Youth in Residential Placements

:::

The inquest into Jeffrey Baldwin's death was supposed to shed light on the child welfare system and prevent more needless child deaths. Baldwin's inquest jury made 103 recommendations. Sep 06, 2013.

Nearly six months after the inquest into the death of Katelynn Sampson began, jurors delivered another 173 recommendations. APRIL 29, 2016.

276 OFFICIAL REASONS FOR CONCERN ABOUT CHILDREN IN CARE.

The Star obtained the reports in a freedom of information request and compiled them according to the type of serious event that occurred — something the ministry does not do.

They note everything from medication errors to emotional meltdowns to deaths.

Restraints were used in more than one-third of 1,200 serious occurrence reports filed in 2013 by group homes and residential treatment centres in the city, according to a Star analysis.

At one treatment facility, 43 of the 119 serious occurrence reports filed to the Ministry of Children and Youth Services include a youth being physically restrained and injected by a registered nurse with a drug, presumably a sedative.

How is a society that's against spanking isn't against tying children to their beds and drugging them?

The language used by some group homes evokes an institutional setting rather than a nurturing environment. When children go missing, they are “AWOL.” In one instance in which a child acted out in front of peers, he was described as a “negative contagion.” Often, the reasons for behaviour are not noted. Children are in a “poor space” and are counselled not to make “poor choices.”

Blame is always placed on the child.

Their stories are briefly told in 1,200 Toronto reports describing “serious occurrences” filed to the Ministry of Children and Youth Services in 2013. Most involve children and youth in publicly funded, privately operated group homes.

:::

2014: Use of 'behaviour-altering' drugs widespread in foster, group homes.

Almost half of children and youth in foster and group home care aged 5 to 17 — 48.6 per cent — are on drugs, such as Ritalin, tranquilizers and anticonvulsants, according to a yearly survey conducted for the provincial government and the Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies (OACAS). At ages 16 and 17, fully 57 per cent are on these medications.

In group homes, the figure is even higher — an average of 64 per cent of children and youth are taking behaviour-altering drugs. For 10- to 15-year-olds, the number is a staggering 74 per cent.

HOW DO CHILDREN END UP MEDICATED? THE WORKER TELLS THE DOCTORS WHAT THEY NEED TO HEAR...

The figures are found in “Looking After Children in Ontario,” a provincially mandated survey known as OnLAC. It collects data on the 7,000 children who have spent at least one year in care. After requests by the Star, the 2014 numbers were made public for the first time.

“Why are these kids on medication? Because people are desperate to make them functional,” Baird says, and "there’s so little else to offer."

Psychotropic drugs are being prescribed to nearly half the Crown wards in a sample of Ontario children's aid societies, kindling fears that the agencies are overusing medication with the province's most vulnerable children.

According to documents obtained by The Globe and Mail under Ontario's Freedom of Information Act, 47 per cent of the Crown wards - children in permanent CAS care - at five randomly picked agencies were prescribed psychotropics last year to treat depression, attention deficit disorder, anxiety and other mental-health problems. And, the wards are diagnosed and medicated far more often than are children in the general population.

"These children have lots of issues and the quickest and easiest way to deal with it is to put them on medication, but it doesn't really deal with the issues," said child psychiatrist Dick Meen, clinical director of Kinark Child and Family Services, the largest children's mental health agency in Ontario.

"In this day and age, particularly in North America, there's a rush for quick fixes. And so a lot of kids, especially those that don't have parents, will get placed on medication in order to keep them under control."

Psychiatric drugs and children are a contentious mix. New, safer drugs with fewer side effects are the salvation of some mentally ill children. But some drugs have not been scientifically tested for use on children, and recent research has linked children on antidepressants with a greater risk of suicide.

Yet the number of children taking these drugs keeps rising, even in the population at large.

Pharmacies dispensed 51 million prescriptions to Canadians for psychotropic medication last year, a 32-per-cent jump in just four years, according to pharmaceutical information company IMS Health Canada. Prescriptions sold for the class of antidepressants, including Ritalin, most prescribed to children to tackle such disorders as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) rose more than 47 per cent, to 1.87 million last year; a new generation of antipsychotic medication increasingly prescribed to children nearly doubled in the same span, climbing 92 per cent to 8.7 million prescriptions.

And with close to half of Crown wards on psychotropic medication, their numbers are more than triple the rate of drug prescriptions for psychiatric problems among children in general.

With histories of abuse, neglect and loss, children in foster care often bear psychological scars unknown to most of their peers. But without a doting parent in their corner, they are open to hasty diagnoses and heavy-handed prescriptions. Oversight for administering the drugs and watching for side effects is left to often low-paid, inexperienced staff working in privately owned, loosely regulated group homes and to overburdened caseworkers legally bound to visit their charges only once every three months.

Unease over the number of medicated wards of the state is growing: This September, when provincial child advocates convene in Edmonton for their biannual meeting, the use of medication to manage the behaviour of foster children across Canada will be at the top of their agenda.

STORY CONTINUES:

:::

What’s worse is that the number of children prescribed dangerous drugs is on the rise. Doctors seem to prescribe medication without being concerned with the side-effects.

Worldwide, 17 million children, some as young as five years old, are given a variety of different prescription drugs, including psychiatric drugs that are dangerous enough that regulatory agencies in Europe, Australia, and the US have issued warnings on the side effects that include suicidal thoughts and aggressive behavior.

According to Fight For Kids, an organization that “educates parents worldwide on the facts about today’s widespread practice of labeling children mentally ill and drugging them with heavy, mind-altering, psychiatric drugs,” says over 10 million children in the US are prescribed addictive stimulants, antidepressants and other psychotropic (mind-altering) drugs for alleged educational and behavioral problems.

In fact, according to Foundation for a Drug-Free World, every day, 2,500 youth (12 to 17) will abuse a prescription pain reliever for the first time (4). Even more frightening, prescription medications like depressants, opioids and antidepressants cause more overdose deaths (45 percent) than illicit drugs like cocaine, heroin, methamphetamines and amphetamines (39 percent) combined. Worldwide, prescription drugs are the 4th leading cause of death.

“There are lots of kids in group homes all over Ontario and they are not doing well — and everybody knows it,” says Kiaras Gharabaghi, a member of a government-appointed panel that examined the residential care system in 2016.

After apprehensions the Children’s aid societies deal with children and youth who have higher levels of mental-health and behavioral problems than the general population. Still, there is evidence of a system using medication simply to keep children and youth under control.

:::

“It is stunning to me how these children... are rendered invisible while they are alive and invisible in their death,” said Irwin Elman, Ontario’s advocate for children and youth. Between 90 and 120 children and youth connected to children’s aid die every year.

“There are lots of kids in group homes all over Ontario and they are not doing well — and everybody knows it,” says Kiaras Gharabaghi, a member of a government-appointed panel that examined the residential care system in 2016.

Between 2008 and 2012 the PDRC choose to review the deaths of 215 children in care. In 92 of those cases the cause of death could not be determined while the majority of the remaining deaths were listed as homicides, suicide and accidental. The PRDC reported during that same time period only 15 children with pre-existing medical conditions in care had died of unpreventable natural causes.

158 CANADIANS SOLDIERS DIED IN AFGHANISTAN BETWEEN 2002 AND 2011 FIGHTING FOR WHAT?

Canada in Afghanistan - Fallen Canadian Armed Forces Members.

One hundred and fifty-eight (158) Canadian Armed Forces members lost their lives in service while participating in our country’s military efforts in Afghanistan. You can click on the names to explore their entries in the Canadian Virtual War Memorial.

How did 92 children in care die between 2008/2012 according to the Ontario PDRC report? The PDRC say it's a complete mystery and no further investigation is required.

Between 2008/2012 natural causes was listed as the least likely way for a child in care to die at 7% of the total deaths reviewed while "undetermined cause" was listed as the leading cause of death of children in Ontario's child protection system at only 43% of the total deaths reviewed.

:::

MOTHERISK REPORT.

To recognize the broad harm caused by the unreliable Motherisk hair testing, the Commission considered “affected persons” to include children, siblings, biological parents, adoptive parents, foster parents, extended families, and the bands or communities of Indigenous children.

This Report is dedicated to everyone who was affected by the testing.

:::

The expert panel convened by Ontario chief coroner Dirk Huyer found a litany of other problems, including:

A lack of communication between child welfare societies.

Poor case file management.

An "absence" of quality care in residential placements.

Evidence that some of the youths were "at risk of and/or engaged in human trafficking."

Eleven of the young people ranged in age from 11 to 18. The exact age of one youth when she died wasn't clear in the report.

Grassy Narrows teen's death to be part of 'expert review' of youth who died in child welfare care

:::

Ontario's foster parents and group home workers celebrate as Doug the Slug Ford's conservative government the closes the child advocate's office..

Ontario’s child advocate had 27 on-going investigations into foster homes as province shuts him down. National News | November 20, 2018 by Kenneth Jackson. APTN News.

After first dealing with the shock of learning through the media that his office was being axed by the Ford government, Ontario’s child advocate’s focus shifted and it was not about his future.

Irwin Elman began thinking of the children his office is trying to help.

More so the 27 individual investigations currently on-going into residential care, like group homes and foster care said Elman.

“I have been very clear what I think about this change. I absolutely do not agree with it. Now I have been working, thinking and turning my mind to how we can we preserve all the things we do,” said Elman, 61, Tuesday.

He said right now it is “unclear” what happens to those investigations if he isn’t able to complete them before new legislation is passed that will officially close his office.

“We’re talking to the ombudsman to ensure any investigation that isn’t wrapped up transfers over. We don’t know where the government’s mind is,” said Elman.

“We intend to complete them. Our office expects those investigations will go over if they are not completed. We will fight to ensure that happens.”

He also said more investigations are expected to start and that the province is notified each time one is opened.

Elman couldn’t speak specifically to any individual investigation, just that they are based on complaints his office received into group and foster care homes.

APTN News knows one of them appears to be Johnson Children’s Services (JCS) which operated three foster homes in Thunder Bay when Tammy Keeash died in May 2017.

APTN reported last week that the three homes were closed after Keeash’s death but had been investigated at least seven times within a year of her dying.

This was all found in an on-going court battle between two Indigenous child welfare agencies fighting over jurisdiction. In documents filed as part of the litigation the advocate’s office first wrote Dilico Anishinabek Family Care of its intention to investigate JSC in August 2016. It appears, from the court documents, Dilico asked the advocate’s office to wait until the agency first investigated JSC.

It was then again confirmed in documents the advocate’s office was investigating JSC following Keeash’s death.

“We can’t allow Indigenous children to fall through the cracks of saying ‘oh you called this ombudsman’s office’ and they’ll sit in Toronto and they’ll tell you use a complaints process. Tell that to a 15-year-old First Nations child, to use a complaint process. When our process is we will go out and stand with the child and walk them through some of the options they have to ensure their voices are heard,” said Elman.

“The ombudsman is not used to working with children. The ombudsman doesn’t have any ability, yet, or capacity, yet, to use an Indigenous lens in its work but we have strived to develop one.”

Elman’s term officially ends Friday as the child advocate. Before he learned his office was being closed he was supposed to be attending a meeting with the provincial government Nov. 26 to discuss what the province is going to do about problems with residential care.

He’s unsure if he’ll still be invited to that meeting if he’s told between now and Friday he is no longer the advocate.

The meeting was scheduled after Ontario’s chief coroner released the findings of the so-called expert panel report into the deaths of 12 children living at group or foster homes in Ontario between 2014 and 2017. Eight were Indigenous and included Keeash.

The panel of experts picked by the coroner reviewed each child’s death and provided recommendations after finding the system failed each of them and continues to do so.

But it wasn’t news to those that have been listening for the last 10 years since the child advocate’s office was first opened.

“This is not news,” said Elman of the report. “We supported the process but we were sort of astounded that people pretended like this is the first they ever heard about it.”

Regardless, if it created action by the government Elman supported that.

But the first move the Ontario government publicly made after the report was released in September was to announce the closure of his office.

That means Elman will be the first and last child advocate in the province.

Tags: child advocate, Featured, ford government, foster homes, Ontario, ontario government, tammy keeash, Thunder Bay.

We all want to believe that super secretive nonprofit corporations with the power to decide who deserves to have rights and who doesn't are full of hard-working people committed to protecting children and improving society. But even the most "well-meaning" nonprofits can get into hot water.

Unfortunately the temptation to cover up financial problems AND THE NEEDLESS DEATHS OF CHILDREN IN THEIR CARE can be particularly seductive for nonprofit CAS directors and board members jumping left and right like rats fleeing a sinking ship who are being arrested sued foster home sex cults again along with unqualified group home staff drugging children out of their minds.

:::

In leaked memo, Peel CAS staff asked to keep cases open to retain funding

By Katie Daubs Feature Writer Thu., March 14, 2013

An internal memo from Peel Children’s Aid Society management asks staff not to close any ongoing cases during March, as part of a strategy to secure government funding.

According to the memo, when service volume is lower than projected, there is less money for the CAS.

An anonymous employee is troubled by the memo as it raises concerns about quotas and the impact on Peel families.

:::

Harassment is a form of discrimination. It includes any unwanted behaviour that offends, humiliates, degrades or marginalizes you. Generally, harassment is a behaviour that persists over time. Serious one-time incidents can also sometimes be considered harassment.

CRIMINAL HARASSMENT

Are you worried about your family's security because an overzealous fanatic is:

■ using a lower corporate standard for reasonable grounds for continually launching or reopening investigations into your personal life hoping for a different result …

■ refuses to let you review your file for inaccurate information…

■ ignores or suppresses any information or documentation that indicates happy healthy children…

■ refuses you an opportunity to address concerns…

■ threatens to arbitrary remove your children if you don't allow them to search your home without a warrant or threatens court action to remove your children if you fail sign consent forms and service agreements…

■ interviews your children in school without recording the interview...

■ is contacting you over and over by phone, email and knocking at your door multiple times every day…

■ is watching your home or workplace…

■ is making you or your family feel threatened...

■ is peeking through your windows…

■ or attempts to talk your very young children into unlocking the door for them when they don't think your in the immediate vicinity...

You are experiencing criminal harassment unless it's a CAS worker, is a crime and you can get help...

:::

DEFINITION of 'Protected Cell Company (PCC)

The basic principle behind cell organization is simple: By dividing the greater organization into many multi-person groups and compartmentalizing and concealing information inside each cell as needed, the greater organization is more likely to survive unchanged if one of its components is compromised and as such, they are remarkably difficult to penetrate and hold accountable in the same way the mafia families, terrorist organizations and Ontario's children's aid societies are.

A corporate structure in which a single legal entity is comprised of a core and several cells that have separate assets and liabilities. The protected cell company, or PCC, has a similar design to a hub and spoke, with the central core organization linked to individual cells. Each cell is independent of each other and of the company’s core, but the entire unit is still a single legal entity.

BREAKING DOWN 'Protected Cell Company (PCC)

A protected cell company operates with two distinct groups: a single core company and an unlimited number of cells. It is governed by a single board of directors, which is responsible for the management of the PCC as a whole. Each cell is managed by a committee or similar group, with authority to the committee being granted by the PCC board of directors. A PCC files a single annual return to regulators, though business and operational plans of each cell may still require individual review and approval by regulators.

Cells within the PCC are formed under the authority of the board of directors, who are typically able to create new cells as business needs arise. The articles of incorporation provide the guidelines that the directors must follow.

The current hierarchical corporate structures that dominate our economies have been in place for over 200 years and were notably supported and defined by Max Weber during the 1800s. Even though Weber was considered a champion of bureaucracy, he understood and articulated the dangers of bureaucratic organisations as stifling, impersonal, formal, protectionist and a threat to individual freedom, equality and cultural vitality.

CAS actions are shrouded in secrecy, and media investigations are chilled by CAS (a multi-billion dollar private corporation) lawyers, who claim to be protecting the privacy rights of all involved to the exclusion of all other rights.

The GONE theory holds that Greed, Opportunity, Need and the Expectation of not being caught are what lay the groundwork for fraud. Greed and/or need provides the motive.

:::

“You know your system is based on the flimsiest of foundations when you have absolutely no standards on who can do this work,” adds Gharabaghi, director of Ryerson University’s school of child and youth care.

Regulation of child protection workers by Ontario College of Social Workers and Social Service Workers: CUPE responds.

"Mandatory registration and regulation by the College is not in the best interest of child protection workers and ultimately, not in the best interest of vulnerable children, youth and families."

HOW DO YOU FEEL ABOUT ONTARIO'S CHILD PROTECTION SOCIAL WORKERS TAKING OFF THEIR LANYARDS AND PUTTING ON THEIR UNION PINS TO FIGHT AGAINST PROFESSIONAL REGULATION?

-

Merton coined the term “self-fulfilling prophecy,” defining it as:

“A false definition of the situation evoking a new behavior which makes the originally false conception come true” (Merton, 1968, p. 477).

In other words, Merton noticed that sometimes a belief brings about consequences that cause reality to match the belief. Generally, those at the center of a self-fulfilling prophecy don’t understand that their beliefs caused the consequences they expected or feared—it’s often unintentional, unlike self-motivation or self-confidence.

-

In the psychology of human behavior, denialism is a person's choice to deny reality, as a way to avoid a psychologically uncomfortable truth like child protection in Ontario is a rogue agency gone mad with power.

There are those who engage in denialist tactics because they are protecting some "overvalued idea" which is critical to their identity. Since legitimate dialogue is not a valid option for those who are interested in protecting bigoted or unreasonable ideas from facts, their only recourse is to use these types of rhetorical tactics to give the appearance of argument and legitimate debate, when there is none.

-

The Slippery Slope: A slippery slope argument (SSA), in logic, critical thinking, political rhetoric, and caselaw, is a logical fallacy in which a party asserts that a relatively small first step leads to a chain of related events culminating in some significant (usually negative) effect.

Distinction without a Difference: A distinction without a difference is a type of logical fallacy where an author or speaker attempts to describe a distinction between two things where no discernible difference exists. It is particularly used when a word or phrase has connotations associated with it that one party to an argument prefers to avoid.

Either/Or Fallacy (also called "the Black-and-White Fallacy," "Excluded Middle," "False Dilemma," or "False Dichotomy"): This fallacy occurs when a writer builds an argument upon the assumption that there are only two choices or possible outcomes when actually there are several.

Red Herring: Attempting to redirect the argument to another issue to which the person doing the redirecting can better respond. While it is similar to the avoiding the issue fallacy, the red herring is a deliberate diversion of attention with the intention of trying to abandon the original argument.

False Dilemma Examples: False Dilemma is a fallacy based on an "either-or" type of argument. Two choices are presented, when more might exist, and the claim is made that one is false and one is true-or one is acceptable and the other is not. Often, there are other alternatives, or both choices might be false or true.

Circular Argument: In informal logic, circular reasoning is an argument that commits the logical fallacy of assuming what it is attempting to prove. ... "The fallacy of the petitio principii," says Madsen Pirie, "lies in its dependence on the unestablished conclusion.

Appeal to Ignorance (argumentum ad ignorantiam): Any time ignorance is used as a major premise in support of an argument, it’s liable to be a fallacious appeal to ignorance. Naturally, we are all ignorant of many things, but it is cheap and manipulative to allow this unfortunate aspect of the human condition to do most of our heavy lifting in an argument.

:::

SEE: Regulation of child protection workers by Ontario College of Social Workers and Social Service Workers: CUPE responds: CONTINUED

I am aware that OACAS, the organization that represents my employer, is planning to make it mandatory for me to register with the Ontario College of Social Workers and Social Service

Workers in order for me to do my job.

One of the reasons given for introducing this requirement is that it will provide more oversight Children’s Aid Societies and child protection workers. Regulation through the College is entirely appropriate for social workers who are in private practice and whose work is not overseen by an employer. But I would like to remind [CAS] that my colleagues and I already answer to more than enough people, processes, and outside bodies in the course of our work, as the following list shows:

• CAS in-house management structure, including supervisors, managers, lawyers, and case conferences; (not public)

• a society’s internal standards, policies, procedures and protocols, some of which are governed by the Children and Family Services Act; (not public)

• a society’s internal disciplinary and complaints procedures; (not public)

• Office of the Provincial Advocate for Children and Youth, which has new powers to investigate CAS workers; (defunct)

• ministry audits in almost every area of service, including Crown Ward Reviews and Licensing; (see links below)

• Child and Family Services Review Board, which conducts reviews and hearings of complaints against a CAS worker; (by the ministry that funds them so there's no potential for conflicts of interests)

• family courts; (see links below)

• Ontario’s human rights tribunal; (see links below)

• the provincial auditor general; (see links below)

• child death reviews, including the Paediatric Death Review and internal reviews; (see links below)

• coroner’s inquests. (see links below)

How could anyone look at this list and possibly think that child protection workers need more oversight?

How about the long list of well publicized scandals ,tragedies, a one sided court system, fake experts, fake drug tests, sex cults and unexplained child deaths in care?

SEE LINKS BELOW

Asking for more ways to regulate and oversee the work of child protection workers is clearly unnecessary and leads me to think there is another agenda at work in this exercise.

I wanted to share some facts and figures that I have learned along the way; I think they point to significant problems for the sector and for [CAS] in particular:

Common sense is sound practical judgment concerning everyday matters, or a basic ability to perceive, understand, and judge that is shared by nearly all people. The first type of common sense, good sense, can be described as "the knack for seeing things as they are, and doing things as they ought to be done."

• There are over 5,000 child protection workers in Ontario

• The College regulates about 17,000 social workers and social service workers

• In Ontario, only 7% of College-registered social workers are employed by a CAS

• Only 4% of members of the Ontario Association of Social Workers work for a CAS

• Between 30% and 50% of Ontario’s child welfare workers do NOT hold a BSW

• Only 63% of direct service staff in CASs have a BSW or MSW (in 2012, it was 57%)

• Only 78% of direct service supervisors have a BSW or MSW (in 2012, it was 75.5%)

• The 2013 OACAS Human Resources survey estimates that ONLY 70% of relevant CAS job classifications would qualify for registration with the College leaving over 1000 unqualified workers shrouded in secrecy roaming loose in our communities.

• From 2002 to 2014, 41 child welfare employees who did not hold a BSW or MSW submitted equivalency applications to register as social workers; only 16 were successful and 25 were refused. (if that isn't a reason for concern - what is?)

Multidisciplinary child protection teams are a strength. Working alongside child protection workers who have taken a couple of years of education in psychology, sociology or mental health enriches the services they provide to children, youth and families, as well as the working environment we all share.

Similarly, those colleagues with backgrounds in such areas as children and youth justice offer insight and knowledge that would not normally form part of BSW or MSW. Sometimes a colleague has gained qualifications outside the country and brings unique cultural or community perspectives to our work.

What happens when those with backgrounds in youth justice start acting like they have BSW/MSW education in psychology, sociology or mental health?

Currently, workplace disciplines, complaints and other personnel matters at [CAS] are treated confidentially. But if child protection workers become subject to regulation by the College, previously confidential workplace matters will become matters of public record.

My membership in the College would mean that anyone can see information about my status or complaints made against me – and under the College’s rules, there is no time limit in which to make a complaint. Disciplinary hearings are open to the public and once a complaint is made, it is on file forever.

There is no process for appeal.

Employers must also file a written report with the College if one of its registered members is terminated. This requirement conflicts with an employee’s right to grieve a termination under the collective agreement or appeal it through arbitration, where a termination may be overturned.

I also have concerns for my personal safety and that of my family, since college registration is open to public scrutiny and provides no protection from potentially violent clients.

None of the ways that the College deals with personal information, complaints, and discipline allow for a fair or safe process for "child protection workers." (ad hominem)

There are any number of measures that can be and ought to be taken to restore public confidence in child protection and keep at-risk children and youth safer. Regulation by the college is not one of them.

I am not a social worker; I don’t want to be a social worker. Had I wanted to be a social worker, I would have trained as one.

If regulation through the College of Social Work is introduced, what will happen to us child protection workers who don’t have degrees in social work (a BSW or MSW) or a social service worker diploma? After all, we make up to 50% of the child protection workforce. (50%)

None of the options currently available to us is appealing: we can try to upgrade to the qualifications that will allow up to keep our jobs. We can move to a different job class. We can accept termination or layoff. (considering the job market what else aren't they qualified to do)

What doesn’t seem to be an option is “grandfathering,” something that would allow child protection workers already in post to keep doing their current jobs. The College is quite specific that grandfathering is not on the table. (so employees with decades of experience are off the table)

These facts seem to present some insurmountable problems for the child protection sector and represent another compelling reason that regulation by the College is a bad move for the child protection sector and for child protection workers.

One of the reasons given for this change is that regulation will result in higher quality services and bring greater professionalism to the field and that this will improve the standard of child protection work in Ontario.

I would like to point out that a failure to meet standards of care in child protection work is very rarely the result of professional misconduct, incompetence or incapacity on the part of individual child protection workers.

The stated purpose of the College is to protect the public from unqualified, incompetent or unfit practitioners.

But children’s aid societies already set those standards and ensure their adherence: they determine the job qualifications. They deal with employees they deem to be unqualified or

incompetent. And CASs decide whether child protection work in their area can be performed by someone who holds a Bachelor’s degree and has child welfare experience.

I may not hold a BSW or MSW degree, enjoy membership in the College or be subject to its regulation. But I feel like professional practitioner in the child protection sector and, as such, I cannot countenance this move toward the regulation of the child protection workforce. I am resolved to fight it at every step of the way and instead campaign for the measures that will bring real benefits to at-risk youth, children and families.

• Regulation with the Ontario College of Social Workers and Social Service Workers is entirely inappropriate for workers subject to employer oversight

• CAS employees are already subject to adequate oversight at several levels

• Without degrees in social work (BSWs or MSWs), many CAS child protection workers aren’t eligible to join the College

• College requirements for members are unfriendly to workers who take breaks from the field, especially women workers

• College discipline procedures require mandatory reporting by employers of an employee’s termination, regardless of whether the termination will be the subject of a grievance or arbitration

• Workers’ safety and privacy is at risk, since a college registration is open to the public

• Regulation shifts responsibility for system failures to individual workers

:::

Under suspicion: Concerns about child welfare.

"Passing the buck..."

CAS funded research indicates that many professionals overreport families based on stereotypes around racial identities. Both Indigenous and Africa-Canadian children and youth are overrepresented in child welfare due to systemic racism but for some reason a document called “Yes, You Can. Dispelling the Myths About Sharing Information with Children’s Aid Societies” was jointly released by the Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario and the Ontario Provincial Advocate.

The document, targeted the same professionals who work with children that CAS research indicated already over-reported families, and was a critical reminder that a call to Children’s Aid is not a privacy violation when a professional claims it concerns the safety of a child.

You can hear former MPP Frank Klees say in a video linked below the very reason the social worker act was introduced and became law in 1998 was to regulate the "children's aid societies."

FORMER ONTARIO MPP FRANK KLEES EXPLAINS A DISTINCTION WITHOUT A DIFFERENCE WORKS.

I'M NOT A SOCIAL WORKER, I'M A CHILD PROTECTION WORKER!

TWO DECADES LATER...

The union representing child protection social workers is firmly opposed to oversight from a professional college and the Ministry of Children and Youth Services, which regulates and funds child protection, is so far staying out of it.

The report Towards Regulation notes that the “clearest path forward” would be for the provincial government to again legislate the necessity of professional regulation, which would be an appallingly heavy-handed move according to OACAS/Cupe.

:::

"Child, Youth and Family Services Act, 2017 proclaimed in force."

The new regulation was updated to only require Local Directors of Children’s Aid Societies to be registered with the College.

The majority of local directors, supervisors, child protection workers and adoption workers have social work or social service work education, yet fewer than 10% are registered with the OCSWSSW.

Unfortunately, many CASs have been circumventing professional regulation of their staff by requiring that staff have social work education yet discouraging those same staff from registering with the OCSWSSW.

Ontarians have a right to assume that, when they receive services that are provided by someone who is required to have a social work degree (or a social service work diploma) — whether those services are direct (such as those provided by a child protection worker or adoption worker) or indirect (such as those provided by a local director or supervisor) — that person is registered with, and accountable to, the OCSWSSW.

As a key stakeholder with respect to numerous issues covered in the CYFSA and the regulations, we were dismayed to learn just prior to the posting of the regulations that we had been left out of the consultation process. We have reached out on more than one occasion to request information about regulations to be made under the CYFSA regarding staff qualifications.

A commitment to public protection, especially when dealing with vulnerable populations such as the children, youth and families served by CASs, is of paramount importance. In short, it is irresponsible for government to propose regulations that would allow CAS staff to operate outside of the very system of public protection and oversight it has established through professional regulation.

Regulations under the CYFSA:

The College has worked with government to address its concerns about regulations under the new CYFSA which set out the qualifications of Children’s Aid Society (CAS) staff. Upon learning in late November that the proposed regulations would continue to allow CAS workers to avoid registration with the College, the College immediately engaged with MCYS and outlined its strong concerns in a letter to the Minister of Children and Youth Services and a submission to the Ministry of Children and Youth Services during the consultation period.

The new regulation was updated to require Local Directors of Children’s Aid Societies to be registered with the College.

We are pleased to note that, while the new regulation does not currently require CAS supervisors to be registered, we have received a "commitment" FROM THE OUTGOING WYNNE GOVERNMENT to work with the College and the Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies toward a goal of requiring registration of CAS supervisors beginning January 2019.

Key concerns:

The absence of a requirement for CAS child protection workers to be registered with the College: ignores the public protection mandate of the Social Work and Social Service Work Act, 1998 (SWSSWA); avoids the fact that social workers and social service workers are regulated professions in Ontario and ignores the College’s important role in protecting the Ontario public from harm caused by incompetent, unqualified or unfit practitioners; allows CAS staff to operate outside the system of public protection and oversight that the Government has established through professional regulation; and fails to provide the assurance to all Ontarians that they are receiving services from CAS staff who are registered with, and accountable to, the College.

Since it began operations in 2000, the OCSWSSW has worked steadily and completely unseen to silently address the issue of child protection workers.

Unfortunately, many CASs have been circumventing professional regulation of their staff by requiring that staff have social work education yet discouraging those same staff from registering with the OCSWSSW.

The new regulation was updated to only require Local Directors of Children’s Aid Societies to be registered with the College.

The majority of local directors, supervisors, child protection workers and adoption workers have social work or social service work education, yet fewer than 10% are registered with the OCSWSSW.

The existing regulations made under the CFSA predated the regulation of social work and social service work in Ontario and therefore their focus on the credential was understandable.

However, today a credential focus is neither reasonable nor defensible. Social work and social service work are regulated professions in Ontario.

Updating the regulations under the new CYFSA provides an important opportunity for the Government to protect the Ontario public from incompetent, unqualified and unfit professionals and to prevent a serious risk of harm to children and youth, as well as their families.

As Minister Coteau said in second reading debate of Bill 89, "protecting and supporting children and youth is not just an obligation, it is our moral imperative, our duty and our privilege—each and every one of us in this Legislature, our privilege—in shaping the future of this province."

A "social worker" or a "social service worker" is by law someone who is registered with the OCSWSSW. Furthermore, as noted previously, the Ontario public has a right to assume that when they receive services that are provided by someone who is required to have a social work degree (or a social service work diploma), that person is registered with the OCSWSSW.

The OCSWSSW also has processes for equivalency, permitting those with a combination of academic qualifications and experience performing the role of a social worker or social service worker to register with the College.

These processes address, among other things, the risk posed by "fake degrees" and other misrepresentations of qualifications, ensuring Ontarians know that a registered social worker or social service worker has the education and/or experience to do their job.

The review of academic credentials and knowledge regarding academic programs is an area of expertise of a professional regulatory body. An individual employer will not have the depth of experience with assessing the validity of academic credentials nor the knowledge of academic institutions to be able to uncover false credentials or misrepresentations of qualifications on a reliable basis.

Setting, maintaining and holding members accountable to the Code of Ethics and Standards of Practice. These minimum standards apply to all OCSWSSW members, regardless of the areas or context in which they practise. Especially relevant in the child welfare context are principles that address confidentiality and privacy, competence and integrity, record-keeping, and sexual misconduct.

Maintaining fair and rigorous complaints and discipline processes. These processes differ from government oversight systems and process-oriented mechanisms within child welfare, as well as those put in place by individual employers like a CAS. They focus on the conduct of individual professionals.

Furthermore, transparency regarding referrals of allegations of misconduct and discipline findings and sanctions ensures that a person cannot move from employer to employer when there is an allegation referred to a hearing or a finding after a discipline hearing that their practice does not meet minimum standards.

Submission-re-Proposed-Regulations-under-the-CYFSA-January-25-2018. OCSWSSW May 1, 2018

If you have any practice questions or concerns related to the new CYFSA, please contact the Professional Practice Department at 416-972-9882 or 1-877-828-9380 or email practice@ocswssw.org.

:::

Between 2008/2012 natural causes was listed as the least likely way for a child in Ontario's care to die at 7% of the total deaths reviewed (15 children) while "undetermined cause" was listed as the leading cause of death of children in Ontario's child protection system at "43%" of the total deaths reviewed (92 children).

2009: Why did 90 children in care die?

Discredited hair-testing program harmed vulnerable families across Ontario, report says.

2013: Nancy Simone, a president of the Canadian Union of Public Employees local representing 275 workers at the Catholic Children’s Aid Society of Toronto, argued child protection workers already have levels of oversight that include unregistered unqualified workplace supervisors, family court judges, coroners’ inquests and annual case audits by the ministry and the union representing child protection workers is firmly opposed to ethical oversight from a professional college, and the Ministry of Children and Youth Services, which regulates and funds child protection, is so far staying out of the fight.. Nancy Simone says, “Our work is already regulated to death.”

YET BAD THING KEEP HAPPENING TO CHILDREN...

A sociopath is a term used to describe someone who has antisocial personality disorder (ASPD). People with ASPD can't understand others' feelings. They'll often break rules or make impulsive decisions without feeling guilty for the harm they cause. People with ASPD may also use “mind games” to control friends, family members, co-workers, and even strangers. They may also be perceived as charismatic or charming.

:::

Head of Motherisk probe had ties to Sick Kids

By JACQUES GALLANT Staff Reporter

Fri., Feb. 12, 2016

Questions are being raised about the retired judge chosen by the provincial government to head a two-year commission reviewing child protection cases that used flawed hair-test results from the Hospital for Sick Children’s Motherisk laboratory.

Justice Judith Beaman has prior legal connections to Sick Kids, the Star has learned. While working as a lawyer in private practice in the late 1980s and early 1990s, she advised the hospital’s Suspected Child Abuse and Neglect team.

Justice Judith Beaman, who will lead the second Motherisk commission.

The SCAN team would later come under fire for its actions during that period, after a public inquiry looked into cases by disgraced pathologist Charles Smith, who worked closely with SCAN members and whose findings led in some instances to wrongful convictions.

“The government has complete confidence that Justice Beaman’s career and experience as a judge and a lawyer will not place her in a conflict with respect to her responsibilities as commissioner,” said Christine Burke, a spokeswoman for Ontario Attorney-General Madeleine Meilleur.